“’You can’t alter the past,’ Cart said. ‘The only thing you can alter is the future. People write stories pretending you can alter the past, but it can’t be done. All you can do to the past is remember it wrong or interpret it differently, and that’s no good to us.’” –The Time of the Ghost, 107

Diana Wynne Jones has written many wonderful fantasy and SF novels for readers of all ages, all of which are remarkable for their depth and complexity. Jones’ fiction is frequently categorised as YA, but she never patronises her young audience, providing them with works that can be as challenging as they are rewarding. All her books work brilliantly on the level of a story well told, but they are full of resonances and allusions that one tends to pick up on when rereading, careful attention revealing the level of care and craft that has gone into constructing the story.

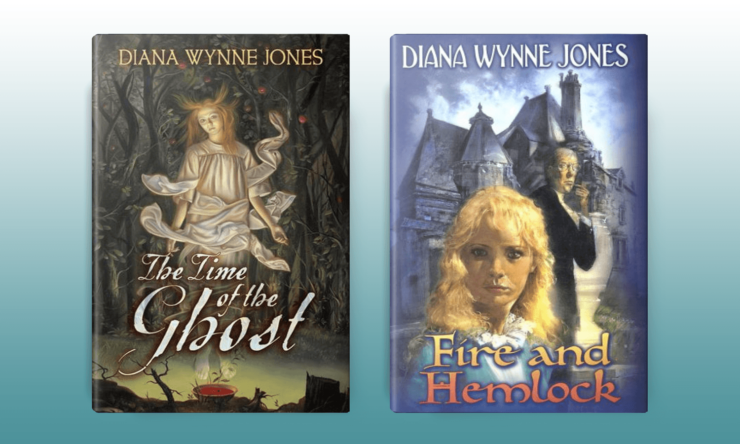

Although Jones is probably best known for her beloved series, including Howl’s Moving Castle (1986) and its sequels and the Chrestomanci books, my favourite examples of her work are two of her standalone fantasy novels from the 1980s, The Time of the Ghost (1981) and Fire and Hemlock (1985). Both of these novels, for me, best demonstrate Jones’ unique strengths as a writer. They are instantly engaging stories with an original approach to their fantastic elements that make them incredibly fun reads. But they are also complex meditations on memory and storytelling itself, works that repay rereading and playfully engage with a dizzying array of other texts. It is this that makes them such enduring works of 20th century fantasy fiction.

The Time of the Ghost is a bold and surprising take on both the ghost story and the timeslip novel. The novel opens with its protagonist not knowing who they are or what has happened to them, just that there’s been some kind of accident which has left them a ghost, and that they know that they are one of the four Melford sisters—Cart, Sally, Imogen and Fenella. Sent back in time to the girls’ childhoods, the ghost must figure out who they are and what happened to them so they can avert a disaster in the future. The unusual setup gives us a protagonist who doesn’t know who she is and has very limited ability to influence her surroundings, which in the hands of a lesser writer could be alienating. However, the distancing effect of using the ghost as the viewpoint character is countered by Jones’ wonderful characterisation of everyone else in the novel.

Each of the Melford sisters is wonderfully drawn. From the moody but caring eldest sister Cart, to the selfish and driven Sally, to the artistic and emotional Imogen, to the rebellious and wonderfully chaotic youngest sister Fenella, each stands as a compelling character with well realised strengths and flaws. And their interactions are wonderfully observed. Anyone who has grown up with a sibling will recognise the mixture of antagonism and affection the sisters show towards each other. The boys with whom the sisters interact—all students from the boarding school run by the girls’ parents–are equally well drawn, from the lovable Will Howard and Ned Jenkins to the unpleasantly slimy and smug Julian Addiman.

The Time of the Ghost mixes these beautifully observed reflections on childhood with a supernatural plot that becomes more sinister and tense as the novel progresses. The Melford sisters invented a game of worshipping Monigan, a ratty old doll. It soon transpires, however, that the rituals they were using have awakened a very real and sinister ancient spirit that inhabits the land, and their childish games of seances and blood sacrifice have had horrifying and unanticipated consequences, as Monigan returns seven years in the future to claim the life promised to her. Jones expertly shifts between alternately moving and hilarious depictions of the sisters’ childhoods and genuinely terrifying folk horror.

Fire and Hemlock is Jones’ retelling of the Child ballads Tam Lin and Thomas the Rhymer, two traditional folk songs from the Scottish borders about young men who are spirited away by the Fairy Queen. Jones’ novel transports the ballads to the modern day, telling the story of Polly, a girl who has two sets of memories, one entirely mundane, and one tinged with the fantastical. In the latter, she meets Tom Lynn when she accidentally gatecrashes a funeral on Halloween, and the two strike up a friendship based on their mutual love of stories. As Polly grows up, her life is punctuated by meetings with Tom, where the fantastical stories they make up together uncannily come true. Polly has made a terrible mistake which has led to Tom being erased from her memories, and she must follow the clues embedded in the stories they have shared together in order to save Tom from being sacrificed as the fairies’ tax to Hell.

Fire and Hemlock is remarkable for how it manages to effortlessly interweave the mundane and the fantastical. Polly’s life growing up, from the breakup of her parents’ marriage to her school days, is recounted in such vivid, realistic detail that when the fantastical encroaches, the reader has no choice but to believe in it. Tom Lynn’s curse is a twist on Thomas the Rhymer’s. Whilst the old folk hero, upon returning from fairyland, is given the gift of only being able to speak the truth, Tom’s gift is that the stories he and Polly make up become reality. Thus, Fire and Hemlock is a book about the power of storytelling. Jones traces Polly’s emotional and physical growth through the books that Tom sends her to read, starting with children’s classics like The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe and Five Children and It and moving through Alexandre Dumas and Tolkien to studies on mythology and folklore like The Golden Bough. Tom proffers these books because of his and Polly’s shared passion for stories, but as he tells her, also for another, more secret reason:

“Only thin, weak thinkers despise fairy stories. Each one has a true, strange fact hidden in it, you know, which you can find if you look.” (144)

These books act as a crash-course on the early history of fantastical fiction for the reader, and for Polly they act as a series of clues that allow her to work out Tom’s predicament with the fairies, something that Tom cannot tell her directly. By the time she comes to confront Laurel, Tom’s ex-wife and the Fairy Queen, and Laurel’s consorts, Morton Leroy and his snotty son Seb, she is so steeped in fairy tales that she has an innate understanding of the rules and rhythms of these stories, giving her a fighting chance at saving Tom.

The Time of the Ghost is a personal novel that features glimpses into Jones’ own life growing up. The home situation of the Melford sisters, whose parents are so busy running a boarding school that they are largely left to fend for themselves, reflects Jones’ family with her absent parents and her close relationship with her sisters. It also features chilling depictions of abuse, with the Melford children left to steal food from the school kitchen in order to eat, a mother who doesn’t notice when one of her daughter’s goes missing, and a father who beats his daughters, swears at them, and can’t recognise them from each other. Jones also explores the adult Sally Melford’s abusive relationship with her boyfriend Julian Addiman. It’s a novel that does not shy away from depicting some very dark subject matter in very realist terms.

Similarly, Fire and Hemlock depicts Polly’s troubled relationship with her parents, her paranoid and self-absorbed mother Ivy and her flaky and unreliable father Reg, and the fallout from their divorce. This comes to a head when Ivy, suspecting Polly of sabotaging her relationship with their lodger, kicks Polly out of her house and sends her to live with Reg, who (with typical negligence) hasn’t told his new partner that Polly is meant to be living with them, leaving Polly wandering the streets of Bristol with no money or shelter. The domestic struggles that Polly and the Melford sisters deal with anchor the two books in very real childhood traumas. The supernatural threats Jones’ characters face are all the more frightening for how they emerge from and interact with these traumas.

On a deeper level, both Fire and Hemlock and The Time of the Ghost are linked by how they approach memory and storytelling. Jones understands that memory is a malleable, unreliable thing, shaped by the stories we tell about ourselves as part of the process of making sense of our place in the world. Fire and Hemlock is largely told in flashback, as Polly explores her lost memories of Tom Lynn and compares them to her more mundane remembered life. The ghost in The Time of the Ghost, having lost her memories, is given a unique perspective to look back on her childhood almost as a participant but without knowing which one she is, which allows her to see all of the sisters with the advantage of distance. Although she is brought back into the silly squabbles and arguments, she is able to see more clearly each of the four girls as individuals with their own strengths and flaws, coping with adversity as well as they can.

Although Cart may argue, in the passage quoted at the start of this essay, that remembering the past wrongly or interpreting it differently is no good, this is the precise mechanism that both Monigan in The Time of The Ghost and Laurel in Fire and Hemlock use to exert their power over the protagonists. How we interpret stories is important, particularly when it comes to the stories we tell ourselves. Both the ghost and Polly have made a terrible mistake in their past, and their separation from their true memories comes from their inability to acknowledge this mistake. The process of them reclaiming their true memories (and therefore their true identities) involves them reclaiming their mistakes and accepting responsibility for them so that they can go on to fix them.

Both novels are also very much about heroism. Throughout both narratives, Jones questions what makes a character heroic, and what it means to be a hero. Moreover, much of Jones’ work is fiercely feminist, and in both The Time of the Ghost and Fire and Hemlock she thoughtfully and deliberately focuses our attention on the lives and experiences of her female characters—Polly and the Melford sisters—and their struggle to claim agency for themselves. Much of the tension in both novels is driven by how their protagonists, as girls and children, are denied agency, and must use their wits and cunning to fend for themselves, both in their abusive domestic situations and against the terrifying supernatural forces they must face. In Fire and Hemlock, Polly and Tom explore different types of heroism through the stories they tell each other, with Polly learning important lessons about the consequences of her actions and the danger of slipping into bland sentimentality. In The Time of the Ghost, the ghost must learn ways to exercise agency both as one of four sisters growing up in an abusive environment and as a disembodied spirit denied the traditional agency expected of a story’s protagonist. Jones’ explorations of unconventional heroism would recur throughout her work, another wonderful example being Sophie Hatter from Howl’s Moving Castle, transformed into an old woman before her time.

The Time of the Ghost and Fire and Hemlock are meticulously constructed, which helps them to convey the complexity of their ideas. Jones sets out the rules for what the ghost can and can’t do early on:

“That was the funny thing about being disembodied. Her mind did not seem to know anything properly until she was shown it.” (23)

The ghost is unable to remember things until she, like the reader, is directly shown them by the narrative. Thus the ghost and the reader are both placed in the same state of ignorance of the characters and world of the book, allowing Jones to cleverly reveal exactly what she needs to when it’s necessary for the story. Through the ghost’s experiments with trying to influence the world around her, we learn that she can move through objects, travel faster than humans can walk, and with great effort move small objects like pieces of paper. This sets up the parameters of how she can interact with the world, leaving her a very limited set of tools with which to find out the truth she needs to know to save herself and her sisters.

Fire and Hemlock’s structure is even more ambitious. Jones structures the novel around the two ballads, with each chapter opening with a quote from either Tam Lin or Thomas the Rhymer which hints towards the significance of the events covered. But, as she explains in her fascinating essay “The Heroic Ideal – A Personal Odyssey” (1989), which is well worth a read for any of the book’s fans, Fire and Hemlock is also structured around both Homer’s Odyssey—with Polly being the Penelope who must use her wits and cunning to save her itinerant Odysseus Tom—and T. S. Eliot’s poem cycle Four Quartets, which gives the novel its four main parts and informs its meditations on the nature of time. That Jones is able to take all of these complex and disparate elements and weave them into such satisfying stories filled with unique, indelible characters demonstrates is not only a feat of remarkable skill, but continues to set her work apart four decades on. Fire and Hemlock and The Time of the Ghost are both shining examples of precisely this ability—the virtuoso balancing of narrative complexity, thematic depth, and sheer readability—that makes her such an enduring author.

Jonathan Thornton has written for the websites The Fantasy Hive, Fantasy Faction, and Gingernuts of Horror. He works with mosquitoes and is working on a PhD on the portrayal of insects in speculative fiction.